On one ice-cranked night in 1941, prisoners from Stalag VIII-A, a Nazi labor camp in Silesia, gathered in an unheated bathroom to listen to a musical performance. Not only was it the venue, but it was a rare event.

Written by French composer Olivier Messian, the quartet was scored on piano, clarinet, violin and cello. This performance brings a quartet of experimental and modernist movements towards the end of time to the world, and is remembered as one of the most consequential musical premiers of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, in the US, Novacode, the first commercially available polyphonic synthesizer, was recently announced. New technology was often greeted by panic. Will this machine make humans obsolete with their composition?

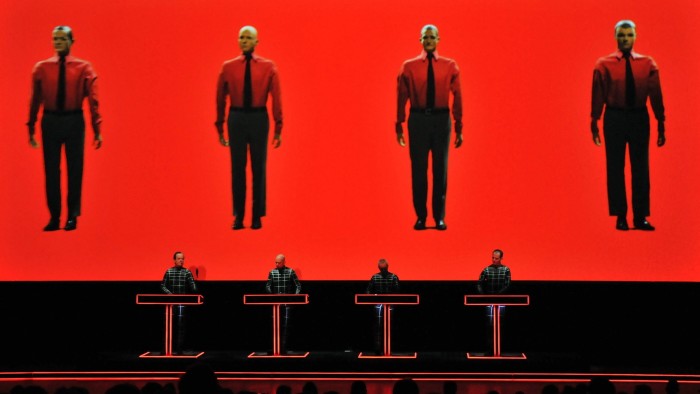

Today we know the answer. Following Novachord, the synthesisers have greatly expanded the sound available to composers and DJs, creating new genres of popular music and becoming an essential tool for music creation. Radiohead’s Kid a has no hip hop or original albums without them. At the same time, today’s musicians are facing new invasion technology, artificial intelligence, with the power to replace voices, bypass education and remove human surveillance.

The more new technology tries to replicate the quality we have identified as humanizing us and creating thoughts, emotions and creation, that is, the more we pretend to act in our image, the more we are more likely to fear it. Still, in order to be free from such concerns at a glance at the art generated by AI, one must look at Saint Bree’s paintings and listen to the Messian quartet. The distinction becomes clear as a day. One artwork brings closer to human expression. The other is a human expression.

How much worry should we be about technical confusion? And one day make creatives obsolete with works of art? These questions have spread as long as people are making machines, but what if they are wrong? Two new books discussed here – David Hajidou and the quartet’s creepy muse for the end of time by Michael Sinmons Roberts – offer a unique approach to exploring how human creativity responds to its changing environment. Can a seemingly existential challenge become a constitutive component of a creative process?

In the End of Time Quartet, in Sinmons’ meditation on his sorrow over his grief over his parents, the story of the Messian quartet, its creation, its historical resonance, its personal meaning for him – is an underground river that comes regularly to the surface. Symmons Roberts has been a longtime British poet, novelist and scriptist, making this book a neat confluence of his talents. It is a novel memoir alongside his own poems that always return to Messiaen’s music. He accidentally discovered the quartet while browsing record shops as a student in the 1980s, and from that moment on became a “lifelong listener” for his work.

Before he internship at camp in his early 30s, Messian’s musical reputation was in the Ascendants in Paris. Symmons Roberts described him as a “mystical modernist composer,” a “Catholic visionary, obsessive scholar,” and fundamentally an independent, contemporary music writer, and this quartet is the best example.

Part of the Symmons Roberts investigation exposes some of the myths surrounding the book of Genesis. For example, it was said that the premiere at the camp was played on a torn, abused instrument. However, according to the EyeWitness account, a new cello was purchased in the nearby town of Görlitz for performance. The fascinating audience of the suffering prisoners was not united in their gratitude. Some people disliked the honesty of the work. And often framed as a response to war, this work was actually inspired by the apocalyptic vision of Saint John’s God in the Book of Revelation. This promised in the Messian’s eyes, “a glorious world of love beyond this world, beyond the end of time.”

These explanations are important. Among other things, Messian did not consider his situation to be restrictive, but of all the prisoners he insisted that he was “probably the only person who was free.” His constrained environment did not diminish his creative work, but reinforced it.

Opened in 2019 at the first show of algorithmic art in New York, Hajdu’s Lively The Uncanny Muse traces the relationship between human creativity and mechanical or technological innovation from the second half of the 19th century. Hajdu, an American music critic and professor of journalism, writes, “In the creation of music, the dynamics of the human machine have always been more than philosophical conceit. It was a practical consideration.”

From the advent of self-play pianos in the early 20th century, Andy Warhol’s “auto-play” – machine-based screen printing for creating multiple prints one after another – Hajdu claims that many of the technologies that he first saw in doubt were eventually incorporated into artistic practice to enrich the effectiveness. He eradicated the cultural evolution of machinery in the art in the broader history that most people perceive, such as the development of the B-3 electrical organs in the 1950s, and that became the sound of gospel music. Martin Luther King Jr. preached with electrical organs in the background.

But in 2025 it’s becoming increasingly difficult to see new technology without the bucket of skepticism, and we know that we are in the unknown territory when it comes to generative AI, the people who control it, and the threats to the lives of artists. Meanwhile, the repair tool will use AI to develop its own AI “Dancing” software that can recover historical recordings and bring together interlocked sounds, such as the quarantine of John Lennon’s vocals in the 2023 Beatles “coming” demo, or Wingnut Films, director Peter Jackson’s production company. Meanwhile, there is a risk that music work will decline as production studios increase their use of AI.

Still, it is not Hajidu’s point to alleviate our concerns. It advocates dismissing technological innovation as a threat to authentic human expression, or to celebrate it critically, and advocates for viewing human binaries as “collaboration.” Inventions such as recording technology that performers once feared, by eliminating live performances, have evolved into a sophisticated art form in itself. He quotes sergeant. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is a turntable as a “totem to the recording studio as an instrument” and as a major instrument for “hip hop DJs.” If you like listening to electronic music or buying replica posters at museum gift shops, you probably agree that, rather than contracting artistic possibilities, technology will expand and bring music and other art forms to a larger audience.

Symmons Roberts argues that for Messian, his strange instrumental signs forced him to mix the tones of the quartet in a whole new way. The sound layers were unprecedented, but they worked, making the limited instrumental palette essential to the character of the work, not the obstacle. Just listen to the quartet’s first move, “Liturgie de Cristal,” and you’ll just hear Clarinet play a figure inspired by the percussive piano and the sounds of birds soaring over silky threads. Multi-layered sonic plane. As Sinmons Roberts writes, it is “like stabbing my head into a surreal aviary that sounds like a bird has eaten too many fermented fruits. It’s not just one bird, all the instruments are in it.

Simmons Roberts strives for a connection in which Messian, the “bird song fortune-teller” in natural music, uses the “bird ID app” to identify the individual sounds that make up the dawn chorus outside the house. The technology developed by AI brings him closer to “Eden’s real music” as Messiaen considered Birdsong.

After being released from camp, Messian returns to Paris, becoming one of the most respected composers of the 20th century, living until the age of 83. The latter whirlwind tour passes nearly 150 years of cultural history. For example, Switched-On Bach, a 1968 synthesizer recording of JS Bach by Wendy Carlos, was unaware that he was loved by respected pianist Glenn Gould.

In contrast, Symmons Roberts’ prose is silky and emotional, and he manages to weave some of his music into the deep connections that have been born out of his poems and weave personal strands.

That creativity is constantly interacting with both our expression and our situation. It is a thread connecting two books, and reading them reminds me of Ouripo, a group of experimental French writers who artificially impose constraints to expand their creativity.

Neither book provides solutions, but reading them in parallel offers two ways to the idea that overcoming may not always be the most generative attitude. Rather, its true generative artistic power cultivates ingenuity to utilize the challenges we believe we are facing.

Uncanny Muse: David Hajdu ww norton by David Hajdu by Automata to Ai Music, Art and Machinery £25/$ 32.99, 304 pages

Quartet for the End of Time: Music, Sadness, Birds Singing Michael Sinmons Roberts Jonathan Cape £20, 304 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FTCBooks Café and follow FT weekends on Instagram and X