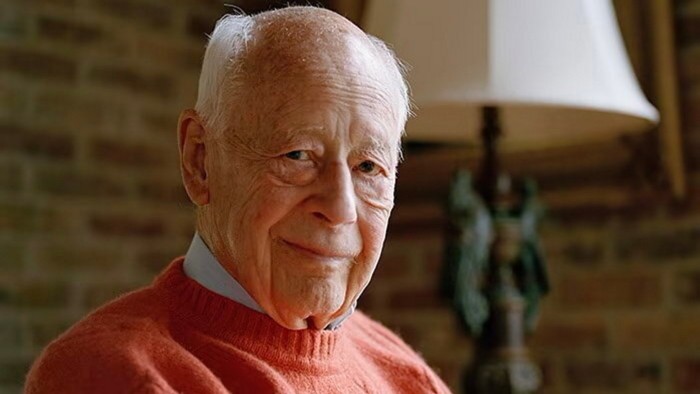

Author, thinker and speaker Charles Handy, who died Friday at the age of 92, was one of the few non-Americans worthy of the term “management guru.”

He disliked the term, preferring the tag “social philosopher.” Handy preferred counseling to leadership consulting, and his method of choice was “Socratic dialogue.” This often took place over meals at his homes in Putney and Norfolk, where he and his wife Elizabeth would invite interesting thinkers, writers and businessmen.

But many of Handy’s organizational insights, provided in public lectures and in a series of books and articles, were practical, visionary, and often provocative.

In the 1980s and 1990s, he predicted innovations that are now commonplace in the world of work, including the rise of what is now called the “gig economy,” the proliferation of outsourcing, and the growth of portfolio careers. Even into his old age, he remained a bold and common-sense defender of human values in business and an outspoken critic of the dangers of rampant automation. “If an organization becomes purely digital, it will become a very miserable place, a prison for the human soul,” he said in a 2017 speech.

Handy was born in County Kildare, now the Republic of Ireland, the son of a Protestant archdeacon. He described himself as “the last of the Anglo-Irish” and was entitled to both an Irish and British passport. “Our beginnings certainly shape our endings,” he wrote in his 2006 autobiography, Myself And Other More important Matters. “I feel deep down I’m Irish, but physically and emotionally I belong to Britain, and indeed to Europe.”

At Oriel College, Oxford, he read the Biography of the Great Men, which combined classics, history, and philosophy, adding a foundation of ancient thought to his work. Aristotle’s central concept was eudaimonia, or the search for fulfillment, which Handy interpreted as “doing your best at what you are good at.”

Handy joined Shell International as a marketing executive at a time when the company represented the pinnacle of postwar management best practices. This was his only experience working as an office worker, adding to the depth of his personal story, which he later shaped, distilled, and used to dramatic effect in his writings, lectures, and broadcasts.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Handy was a pioneer in British business education, bringing the relatively novel idea of executive education back to London Business School from his time at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, where he taught a version of the US program. Ta.

But in 1981, he dove into what he would later call the “portfolio life.” He stepped off the teaching treadmill and became a freelancer. The change in direction gave him the time and freedom to write a series of books on modern organizations, including The Age of Unreason (1989) and The Empty Raincoat (1994). I got it. Contradictions and challenges between economic development and workplace change. This transition also involved what he later described as a rewriting of his “marriage contract” with Liz. She resumed her career as a photographer and became Handy’s business manager, agent, and image consultant, making up for Handy’s initial reluctance to charge speaking fees.

Handy’s clear, conversational prose was characterized by his use of vivid metaphors. These include the “shamrock organization,” an early depiction of a network of company staff, contractors, and part-time workers, and the relationship between large multinational corporations and independent workers, drawn from a 2001 book. It included his “elephant and flea” image of a symbiotic relationship. A book with the same name.

In The Second Curve (2015), Handy reprized some of his biggest hits, but also offered a radical take on change in areas as diverse as measuring the economy and organizing Britain’s democracy. It was full of suggestions. He also wrote of his determination as he grew older to “continue to be of interest to the generations below me, with wit and wisdom, sometimes seasoned with thoughtful generosity.” He and Liz, who died in a car accident in 2018, stayed true to that commitment.

Handy also remained a gentle but cunning marketer of his brand. In 2015, when a fan asked him to recommend a new book, Handy replied via email that he would “never write a blurb,” but added that he would be happy to write a foreword. This was a kind of “thoughtful generosity” that led to his name being published in the magazine. cover.

His determination to spread his ideas continued to shine through even after suffering a stroke in 2019. Frustrated by the hospital’s restrictions, he convinced the nurses to paste a note above his bed that read, “Charles Handy is allowed to do whatever he wants.” I planned to write about his experience.

He passed away peacefully at home surrounded by his family. He leaves behind two children, Scott and Kate, and four teenage grandchildren, to whom he dedicated his 2020 book, 21 Letters on Life and Its Challenges.

I continued to do what I was good at with all my might until the end. His final book, The View from Ninety: Reflections on Living a Long, Contented Life, will be published next year.

In 2017, Handy gave the closing speech at the Global Peter Drucker Forum. This conference is a celebration of another passive management guru whom he admired. He concluded by calling for a management revolution. “Let’s start a small fire in the darkness and keep going until it spreads and lights up the whole world with a better vision of what our business can do,” he declared, to a standing ovation. .