At the headquarters of China’s pioneering robotics manufacturer Unitree, visitors are invited to push and kick the G1 (1.3 meters high silver humanoid) to test their balance.

The Hangzhou-based group demonstrates the strength of its efforts to transform early industries into building human-like machines. The robot is equipped with open source software that allows buyers to perform, dance, or perform round house kung fu kicks.

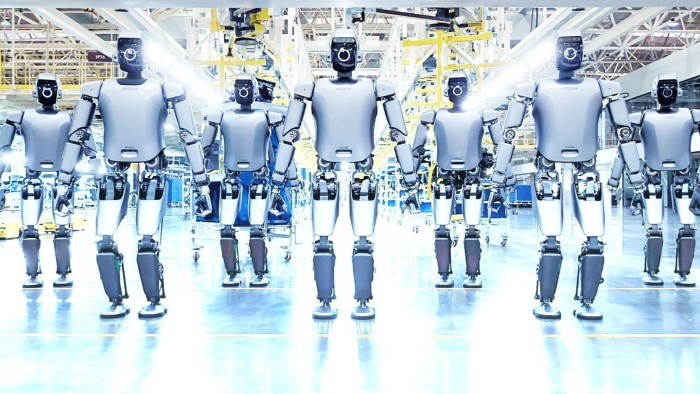

Unitree leads packs of Chinese startups in the sector, including Agibot, Engine AI, Fourier and Ubtech. Over the past few months, it has attracted attention with social media video demonstrations. At China’s Big Spring Festival Gala, 16 Unitree’s H1 bots performed synced folk dances during live shows broadcast to millions of viewers.

This was an impressive illustration of China’s ability to build humanoid hardware that could become a new frontier in the US-China technology competition. Investment bank analysts predict that the sector will be able to produce the next widely adopted device after smartphones and electric vehicles, and Unitree CEO and founder Wang Xingxing believes he has experienced a breakthrough of “iPhone Moment” within five years.

Goldman Sachs expects the global humanoid robot market to be worth $200 billion by 2035. Research analysts at Bernstein estimate annual robot sales of up to 50 million people in 2050.

The US contest includes automaker Tesla, including leading technology companies such as Google and Meta, as well as robot startups such as Boston Dynamics, Figure and Agility Robotics. For now, four big industrial robot manufacturers in Japan and Europe are focusing on building collaborative robots to work with humans rather than creating humanoids.

However, researchers say China’s deep electronics and EV supply chains are already starting a head start for the country, with many of the components of humanoid robots already built domestically and included in electric vehicles.

It includes actuators that convert energy into motion, as well as batteries and vision systems such as Lidar. Still, the US has the main technology of moving parts, and Nvidia AI processors continue to be the brain of most humanoids, analysts say.

“China has very good hardware, but innovation and software (on), and the US still has advantages,” said Johnson Wan, industrial analyst at Jefferies Investment Bank.

However, because components are so cheap in China, Bank of America analysts estimate that content from Tesla’s second-generation Optimus robots would cost about a third if it was used rather than from Chinese suppliers. In one example, 25 Chinese companies offer dexterous hand components compared to just seven in the US.

Low-priced Chinese hardware has begun to open up the field to a number of select labs and startup-focused experiments, such as Massachusetts technology spinoff Boston Dynamics.

“The University of Manchester Robotics has made it a great opportunity to learn about it,” said Bruno Adorno, a robotics reader at the University of Manchester. “It was impossible before Unitree,” he said.

Bernstein analysts say China’s progress is comparable to its dominance in the electric vehicle market. “China acts very quickly in multiplying products and use cases, but it appears that US players are filming for the Holy Grail solution. China is taking a ‘natural selection’ approach with a very diverse product model,” they said in a recent report.

At its annual parliamentary meeting last month, Beijing saw humanoid robotics as a strategic industry and began luxurious funding for start-ups. Unitree founder Wang was recently given an audience with President Xi Jinping. The country’s security forces have experimented with using startup Robodog in their movement, but Unitree emphasizes that it is not selling its products to the Chinese military.

The company has raised funds from well-known investors, including former China VC Arm Hongshan and Delivery Group Meituan from Sequoia Capital. China’s business records show that government funds are also being invested, including China’s Internet Investment Fund and the state-sponsored Beijing Robot Fund, allied with the country’s cyber regulators.

“Ai-powered robots may not only be the future direction of China’s future development, but perhaps the future direction of the whole world,” said Shen Zhen Zhengchang, the country’s parliament representative. “China is striving to dominate the industry,” he told the Financial Times.

The Chinese group is also supported by a well-coordinated industrial policy engine. China’s Ministry of Industry, Information Technology has published an ambitious roadmap for the industry that will create courses to overcome major technical hurdles. The new RMB1TN ($13.7 billion) state-led venture capital fund will add more financial thermal power.

Local governments also provide subsidies to participate, compete and build industrial supply chains. Hangzhou’s government funds are pouring money into the sector, but officials at Shenzhen say they are working on a policy package and have introduced related grants and awards.

Shanghai has established a state-supported training farm for robots. Humanoids repeat certain tasks to obtain the data they need to perform their own operations. The project’s backer, state-owned Shanghai Electric, said it houses 100 humanoids that plan to increase this to 1,000 simultaneous training of general-purpose robots by 2027.

The goal is to lay the foundation for humanoids to keep up with industrial robots built to specialize in handling a single task multiple times and increase factory automation. It provides a commercial humanoid business model with shortages of current use cases at the technology level.

Chen Guishun, the robotics head of Industrial Automation Powerhouse Inovance, based in Shenzhen, said there are high expectations for robots like humans, but the flashy two-legged humanoid type in the video is not viral.

“Bipedal movement is the most expensive solution with less energy efficiency,” he said. “Tracking or wheeled constructions can achieve the same amount of mobility.”

Some local Chinese police forces are beginning to use robodogs and humanoids on their local patrols, but stores are beginning to adopt humanoids for entertainment value. The factory is in the early stages of using humanoid robots on production lines.

For now, Unitree sends most of its robots to universities and labs.

Recommended

Adorno said the company has reduced the cost of procuring its programmable H1 model humanoid robots from $1 million to about $100,000. Unitree was responsible for the code that operated and controlled the motors and sensors for free, allowing the team to build on the platform.

“We are developing new techniques to improve robot behavior and the ability to unleash functionality by connecting to Unitree (application programming interface),” says Adorno.

Markus Fischer, a robotics specialist at German technology consultant Exxeta, said the programming tasks needed to control humanoids are still extensive. He said it would take about 10 days to program the G1, roam freely around the office and sail in his head with a Lidar (a sensor that uses light) instead of a remote control.

While issues such as opening the door remain, Fisher said there is demand from customers who are interested in humanoid entertainment and novel values, such as greeting retail customers.

Additionally, Fisher expects it will be possible to stock up and raise supermarket shelves with food, but he points out that challenges remain.

“It’s very easy to grab things for humans,” he said. “We look at the glass, grab it, know if we put too much force on it, we can break it, but the robots have to be taught to do it.”

These challenging technical challenges made some experts skeptical of the way to commercialize humanoids. Prominent Chinese venture capitalist Allen Tzu recently told local media that his company is withdrawing humanoid investments.

In the hype, he noticed that only one new type of customer has emerged. “State-owned companies buy them for display at the front desk,” he said. “But that’s not the kind of customer we’re looking for.”

Gloria Lee, Nian Liu and Wenzie Ding contributed the report