Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

FT editor Roula Khalaf has chosen her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

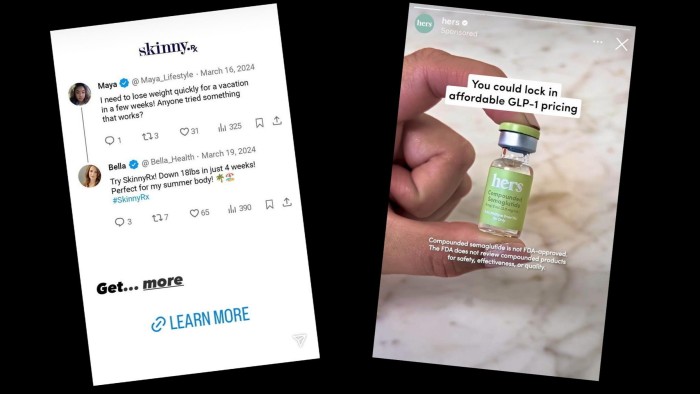

A slender young woman holds a bottle of clear liquid in one hand. The words “skinny” and “GLP-1” appear on the label for a new class of weight loss drugs. Meanwhile, she picks up a pipette filled with liquid and holds it up as if to drop it into her open mouth. “Lose up to 15% of your body weight,” the caption on the Instagram post reads.

This marketing by a little-known online pharmacy called Skinny Rx is one of thousands of ads targeting young women on social media, offering “affordable” anti-obesity and anti-obesity drugs in just an hour. It promises users that they can get their diabetes medication. Just a few clicks.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve noticed that my Instagram feed has been taken over by ads, even though I’ve never purchased drugs. For weight loss drugs, oral liquids or injectables, up to 8 consecutive ads will appear.

Looking at Meta’s Ads Library, it’s clear I’m not alone. There are over 5,000 active ads listed that include the phrase GLP-1, as well as over 3,100 campaigns that mention the GLP-1 drug semaglutide and 4,000 that mention Ozempic. As a comparison, terms for popular beauty products like nail polish and blush had fewer ads, about 3,000 and 1,100, respectively.

The value of these drugs in the treatment of obesity and diabetes is clear. And here in the United States, legitimate prescription drug marketing is legal. But at a time when social media platforms are facing pressure to take greater responsibility for the content users see, experts say it would be irresponsible to allow them to continue bombarding people with ads promoting rapid weight loss. says.

Dozens of studies have already found a strong link between social media, especially photos and videos, and eating disorder pathology. In 2021, whistleblower Frances Haugen leaked Mehta’s own research suggesting that Instagram can have a negative impact on the mental health of some teenage girls. According to one memo, an Instagram employee posed as a 13-year-old girl looking for diet tips and was offered recommendations for accounts called “too skinny” and “applecore anorexic.”

Silicon Valley companies recognize that change is necessary. Meta announced in January that it would restrict young people from viewing content related to eating disorders. However, advertising for weight loss drugs for people over 18 is allowed on the platform.

This marketing epidemic “can lead to an eating disorder, or the person may already have an eating disorder and then really turn to self-harm,” says the National Association for Anorexia and Related Disorders. said association president Maria Lago. .

In addition to touting low prices, many advertising messages suggest that users can easily obtain the drug, even though it must be prescribed and administered by a physician.

I could have clicked on one ad and immediately bought a replacement for Ozempic. Second, they were asked to fill out a questionnaire that included their height and weight. With just a few tweaks to the numbers, the drug was “pre-approved” in no time.

Some advertisements promote so-called “combined” semaglutide products, or custom-made medications that have not been approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulators. “Those (advertisements) are scarier to me,” Rago said, noting they may not be safe.

There are restrictions. Meta’s policy prohibits ads that “create negative self-perceptions” or “exploit insecurities to conform to certain beauty standards.”

Advertising for prescription drugs is already banned in Australia and the UK. Ads for weight loss drugs are not allowed on TikTok. In the United States, the Senate introduced new legislation in September targeting misleading prescription drug advertising.

McKenna Ganz of the Eating Disorders Foundation hopes that without further regulation, social media users will no longer be induced to buy drugs just because they see attractive advertisements. “That’s a decision they should make in consultation with their own doctors,” she says. “It’s not just basically working with social media algorithms.”

hannah.murphy@ft.com