Unlock Editor’s Digest Lock for Free

FT editor Roula Khalaf will select your favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Is it time to redefine what career success means? Rutger Bregman thinks so, and his new book, Moral Ambition, creates an active and persuasive case of throwing away “mind number, meaningless, or merely harmful work” and doing something more meaningful instead. He aims straight for the book to “idealist and ambitious” people of all ages who work in consulting, legal, finance and other high-paying sectors. (Yes, he’s looking at us, ft readers.)

Bregman doesn’t lean forward on himself. The superstar Dutch historian has published several books and essays, including the global bestseller, Humanity: A Hopeful History (2020) and Utopia for Realists. He went viral on YouTube in 2019 after calling the billionaire at Davos’ World Economic Forum for tax avoidance tactics.

In this optimist manifesto, the moral ambition is to “dedicate your working life to the great challenges of our time, whether it’s climate change, corruption, total inequality, or the next pandemic.” Inevitably, David Graver and his notion of “bulky work” emerge early, but Bregman doesn’t stay negative. He wants to bring about positive change in us, and we can start small. He inspires readers through practical examples, as is conventional in modern “change your life” manuals.

Here is a playbook, and establishing or participating in a “driven idealist elite squad” is probably the best way to do that. Examples include Ralph Nader and a team of young lawyers who urged him to work with him on reforming laws on complex issues such as food safety and water pollution in the 1960s in the United States.

Bregman’s unconvincing and persuasive writing style makes deep change easy. It will help you read about successful campaigns. The advances in the anti-slavery movement in Britain are carried out throughout the book (“the abolition movement happened as a kind of Quaker startup”).

Thomas Clarkson, an influential early abolitionist, instead focused on what the country cared about. Approximately 20% of the crew vulnerable to tropical diseases were nearly dying on any voyage. “Yes, one of the biggest abolitionists in history has shifted their focus to suffering among perpetrators, something psychologists call this tactical moral reconstruction.”

The goal is to find new arguments for your globally changing ideas that will convince those who do not share your beliefs. This requires compromise. Bregman has no time for modern activists who drop out of each other and amortize potential allies due to minor accidents and lack of “intersection.”

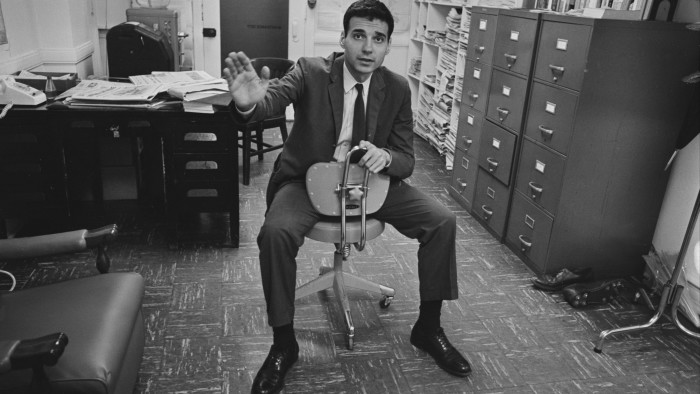

In the early days of moral ambitions, I thought Bregman’s vision of a small number of individuals generating the greatest benefits for people and planets might represent the early battle of the military for good against the increasingly dark influence of the Silicon Valley elite and philosophy. Then, like magic, on page 48, there is an old photo of the original “Paypal Mafia” by venture capitalist Peter Thiel. “History is full of small action groups that have a huge impact,” the author says. “Tiel writes that he can talk about cults.”

Bregman does not suggest that the founders of these high-tech have moral ambitions (“Of course, it’s debate whether they made the world a better place”). He merely points out that single-minded focus, tireless work and commitment to the cause are effective. “If you want to change the world, you’d be better off joining a cult. Or start yourself.”

Recommended

Instead, Bregman’s mission is to show that the more causes under the radar, the more important it is for the smarter person to focus their efforts there. The most memorable example is the story of Rob Mother, a British executive who began organising sponsored swimming to raise money for a girl called Terry, who was burning badly in the fire. Having raised enough money to make her financially safe for her life, he expanded to establish the Malaria Foundation, which distributes nets of insecticide-treated mosquitoes. “What began as Little Terry’s swim has grown into a campaign that saved 100,000 lives by conservative estimates.” AMF is one of the world’s best-performing nonprofits and is built by individuals with moral ambitions, Bregman said.

If Mother hadn’t seen the news report about Terry’s accident in June 2003, this may not have happened. Sometimes it’s a chance or serendipity to take us in a new, unexpected direction. And Bregman makes that sound like the most exciting of all.

Moral Ambition: Stop wasting your talent and starting to make the difference by Rutger Bregman Bloomsbury.

Isabel Berwick works at FT, the editor and author of The Future-Proof Career.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FTCBooks Café and follow FT weekends on Instagram and X