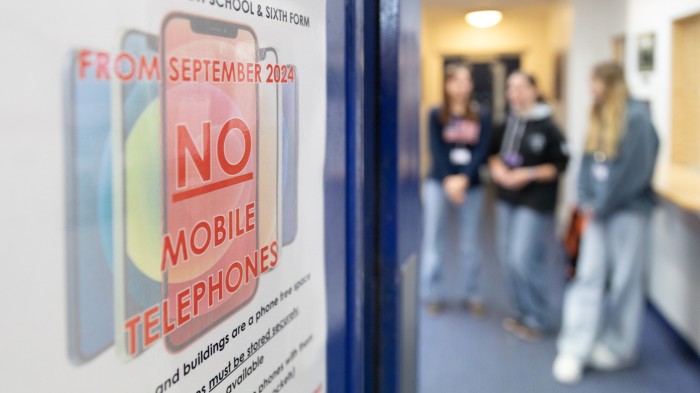

Philip Hirst is the headmaster of a school he proudly calls a “phoneless school.”

Thomas Mills High School in Framlingham, Suffolk, is one of a growing number of schools in England choosing to impose strict rules on smartphones amid growing concerns about the impact on children’s mental health. It is one.

Since September, students ages 11 to 16 have been asked to put their cell phones in lockers upon arrival and keep them there until the final bell.

“The whole idea is that if they’re out of sight, they’re out of mind,” Hurst told the Financial Times. Previously, the 1,000 children at his school were not allowed to look at their phones during class, but they were allowed to keep them in their pockets or school bags.

He said only four mobile phones had been confiscated since the ban was introduced two months ago. “Before, this would have been a common occurrence.”

The death of Molly Russell, the British teenager who took her own life after viewing thousands of online posts about suicide, depression and self-harm, was one of the reasons behind Hearst’s decision to impose the ban. Ta.

“I’m seriously concerned about the mental health effects of the time children spend on their phones,” he says. “We weren’t prepared to just wait for someone to say we needed to take action.”

Almost half of Brits think there should be a complete ban on smartphones in schools, according to an Ipsos poll for the FT.

Of the 2,175 adults surveyed, 48% supported a complete ban on cell phones in school buildings, and 71% supported requiring students to put their phones in their baskets during class.

Of those surveyed, 30% said they think the most acceptable age to give a child a smartphone is between 11 and 12, while 28% said 13 and 14 is a more appropriate age.

A survey conducted by regulator Ofcom in April found that nearly a quarter of children aged five to seven in the UK own a smartphone. A significant number of people were using social media apps such as TikTok and WhatsApp despite being under the minimum age limit of 13 years.

At the same time, a growing body of research is beginning to show how the proliferation of smartphones and social media apps is causing an increase in eating disorders, depression, and anxiety among young people.

In his book The Anxious Generation, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues that smart devices have “rewired childhood.” He believes there should be a complete ban on smartphone use for children under 14.

A study conducted this year by the University of Oxford found that social media use among teenagers is strongly correlated with poorer mental health.

The academics behind the study told the FT they found a “linear relationship” between higher rates of anxiety and depression and time spent networking on social media sites.

For schools, guidance set out by the last Conservative government earlier this year stipulates that each leader will decide their own policy regarding the use of phones. But parents and policymakers are increasingly calling for the ban to be a legal requirement.

“There is growing evidence that smartphones, and in particular social media, are having a negative impact on children’s mental health, sleep and learning,” said Josh McAllister, a Labor MP and former teacher. We would like to promote the use of telephones. A private member’s bill will be passed by the House of Representatives next year.

The government has ruled out backing his proposal to legally mandate free calls to schools. But he said the government was “open-minded” on other parts of the bill aimed at reducing children’s smartphone addiction.

His bill would raise the age at which children can consent to data sharing without parental permission from 13 to 16, which would make it harder for social media companies to “make their content highly addictive.” he says.

The second part of Mr. McAllister’s bill would require that apps’ “compelling design features” (which the lawmaker described as “addictive parts of the design, long scrolls, nudges, notifications”) Expanding Ofcom’s powers to ensure age-appropriate and not age-appropriate. Versions of social media used by children under 16 years of age.

Last month, Wes Streeting, the UK health secretary, told posted, suggesting support from the government.

Ministers will be keeping an eye on developments in Australia. Last week, the Australian government announced a ban on social media sites for children under 16.

Another reason Hurst chose to introduce a phone ban at Thomas Mills High School was because of local parent groups who are calling on schools to play a role in restricting their children’s use of devices. said.

Daisy Greenwell, co-founder of the Smartphone Free Child movement, is also based in Suffolk. The group originally started as a local WhatsApp group of parents who pledged not to give their children a mobile phone until they were 14, but has since split into separate groups across England and grown to 150,000 members. It swelled up.

Mr Greenwell said it was “just a given” that smartphones should be free in all schools. “This gives kids six to seven hours a day to learn and socialize freely, away from Big Tech’s addictive and predatory algorithms,” Greenwell said.

“Teachers say smartphones are a disaster in school settings and a huge waste of time and resources.”

In addition to banning their use during the day, Greenwell wants schools to ban smartphones altogether and use simpler “dumb” phones.

“This instantly levels the playing field and eliminates the insidious network effects of smartphones, which means kids need smartphones just because everyone else has one. I mean,” she said.

The idea appears to be gaining traction with parents, with Virgin Media O2 reporting last month that non-smartphone sales had doubled over the past year, with a “significant spike” in September. did.

Children who violate the no-phone policy at Thomas Mills High School will be detained and their parents will be asked to collect their devices, Hurst said.

“Overall, the ban has responded very positively,” he said. “Children and teachers say there is less disruption in the classroom, more eye contact, and more social engagement. It’s becoming more and more normal for us to know that it’s not the right place to use it.